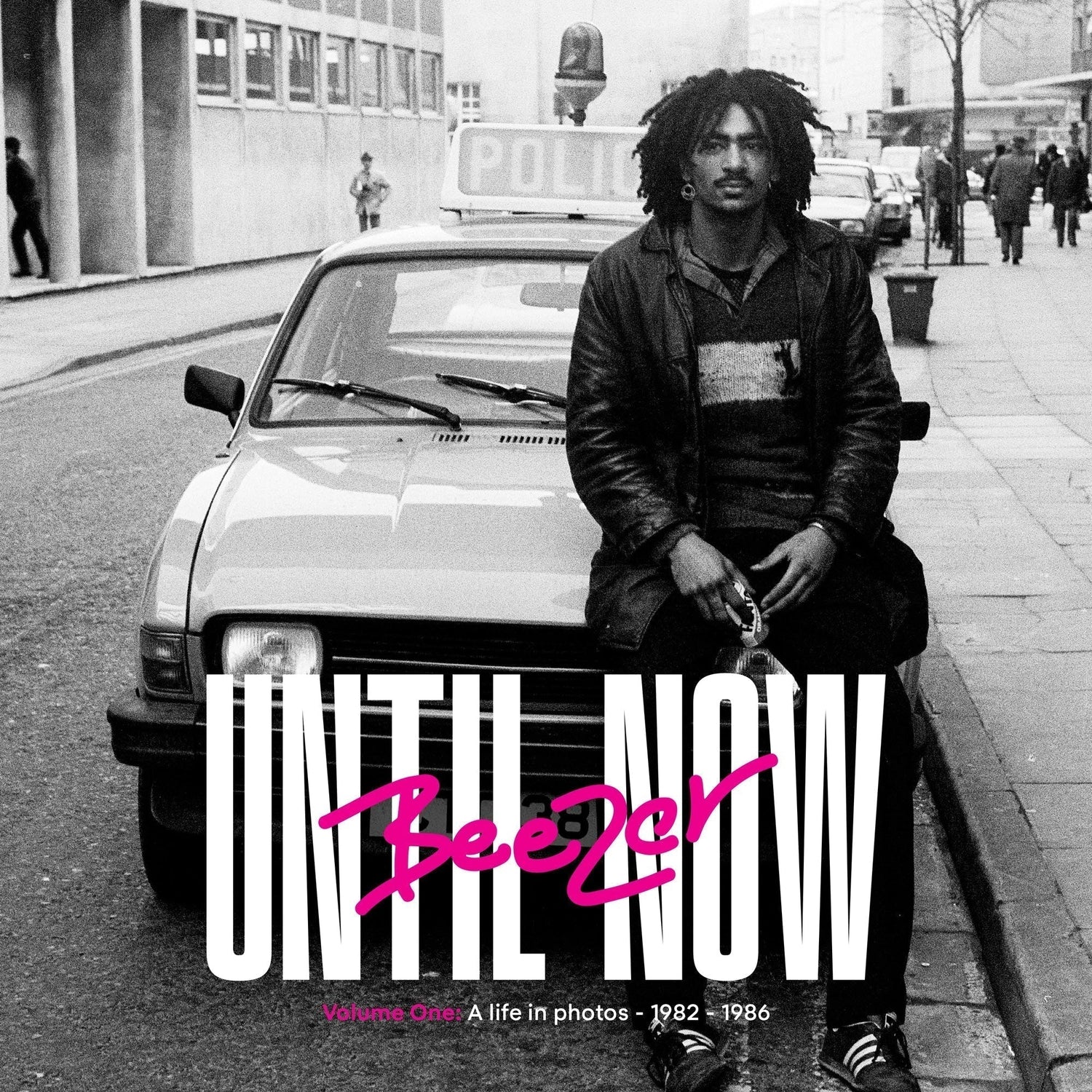

Sludge Magazine chats with Beezer about his career spanning 40 years photographing British social justice movements surrounding the release of new book Until Now: Volume I: A Life in Photos 1982-86.

Every generation of young people has a habit of believing they revolutionised things. In the social media age younger millennials and gen-z could be forgiven for thinking protest was a thing of our own invention given the airtime given to the #MeToo, #BLM and now #FreePalestine, #FreeCongo and calls to boycott Dubai and the UAE. It's important for every generation to take up the mantle and continue advocating for the rights of marginalised people but there's equal importance on remembering what came before us. We are seeing first hand in the here and now how much time and effort governments put into suppressing dissidence, which makes the role of photographers so crucial. Part of the reason we understand the history of counter culture in Britain is the work of photographers like Beezer.

Andy Beese from Bristol has spent the last four decades shooting youth subcultures and organising movements between the U.K. and Japan. His new book Until Now: Volume I: A Life in Photos 1982-86 focuses on 1982-1986. In the midst of Thatcherite policies young people form different pockets of youth culture across communities banded together and birthed a lot of the subcultures that went on to define British culture. We caught up with him to learn more about this landmark release.

Is there any change in your approach based on whether you're shooting someone from the world of music vs. fashion or shooting documentary?

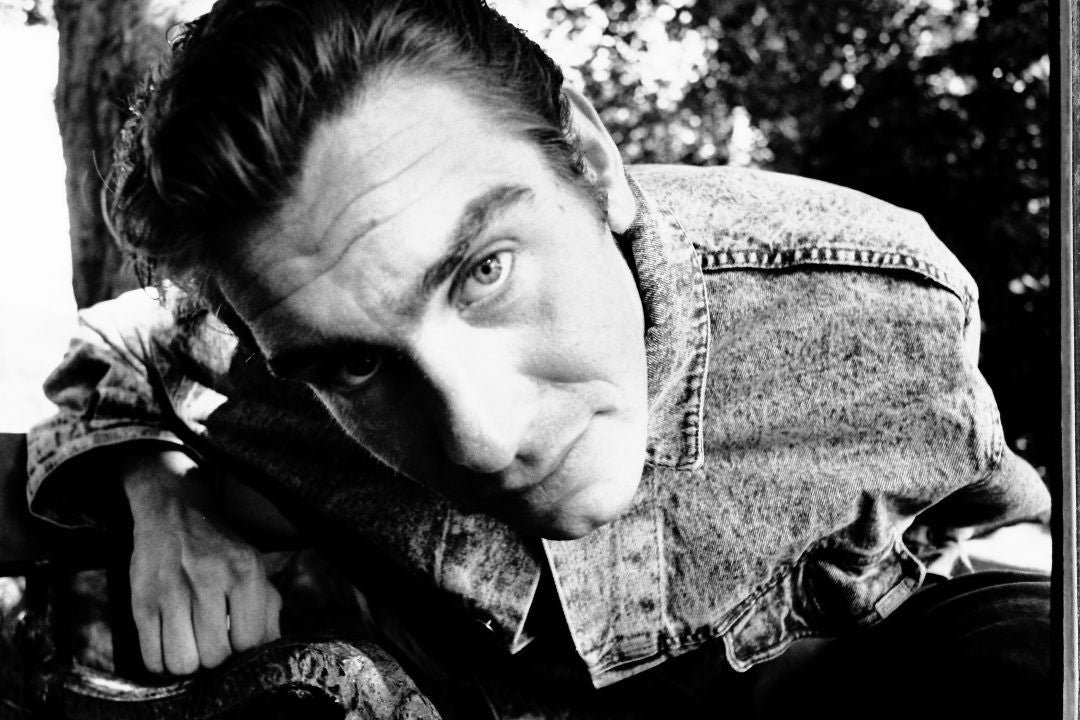

Yes, there is. I take a somewhat different approach to each of the 3 categories you've mentioned. With musicians, I tend to shoot very quickly, especially when they're on the road or they're having a day of press interviews as I feel that they don't want to be bothered by having yet another photographer, but I make the most of a short period of time. As I appeared to work much faster than many of my contemporaries in the analogue days of film, I was referred to as "One Roll, Three Minutes". Until now, it's been good for me as well as the artist and has given me a little bit more time to spend on the rapport with them. With fashion, I don't shoot much fashion per se, but the people I shoot are fashionable in their own right. It was interesting to see after I released my first book, “The Wild Dayz" in Japan that so many kids were trying to dress like the subjects in my book whereas I feel that with my current books “Until Now: Books Alpha & Beta” being released in the UK, viewers & readers are going to look at it from all perspectives - not just the clothing. Whenever I shoot a 'pure` fashion shoot, I tend to express the relationship between the human/the subject and the clothing rather than just the look. With documentary images, I try to be unobtrusive. I endeavour to shoot my subjects in a relaxed and natural setting, by this I mean to make them feel less conscious at all times of a camera being around them.

When you're shooting youth subcultures, have you noticed subjects changing how they respond to you as you've gotten older?

Yes, I noticed it the other week in Bristol when I was revisiting the Thekla. I was trying to recreate a shot that I'd taken over 40 years ago from the exact same position today. The fact that most people now have a camera, themselves, on their phone as opposed to being the only person with a camera at an event where one easily realised anyone with a camera was a professional photographer, these days with everyone being so photo aware it’s a very different environment for a photographer. Being older than the majority of subjects I shoot, I find that the younger people tend to ask what I'm doing and where the images will be going. I reckon subjects were less camera friendly years ago as in those days, possessing a camera was much rarer.

1982-86 is a relatively short focus given your extensive career. Why does the book hone in on these 4 years?

That period was when I started taking photos and I took a lot of important images at that time, documenting scenes that became important cultural events in the history of British music, festival culture, social history and subcultural imagery.

A lot of your work documents counter culture and political dissidence. What are your feelings on the current clamping down on political expression in Britain?

The struggles are similar to back then, but the writing on the wall is the same, the poverty and the difference in what people earn is worse, so I can document how people respond to that.

What is one thing the youth of Britain could learn from the youth of Tokyo and vice versa?

That in Tokyo youth were very interested in the look and the style of things and that in Britain there was always a focus on style with an underlying attitude or set of ideas both can learn from this. Britain created a lot of new youth cultures and Tokyo has been brilliant at performing those youth cultures.

Would you like to be a photographer starting your journey now in 2025?

The biggest change is that you can, once you have a phone, take pictures without the cost of buying film, developing film and thinking about lighting and different lenses, so the technical element is easier, and that means that now it is now more accessible. So in that sense it would be amazing to be starting now, but you have still got to get the right shot and that incredible image.

Article by Martyn Ewoma

Read the full article here: https://www.sludge.online/q-a-with-beezer

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.